Esoteric art

Shomyo

Shomyo widely refers to the act of monks assigning a melody to Buddhist scripture and chanting these tunes are part of esoteric rites.

During travels in search of Buddhist scriptures, Nagarjuna (the third patriarch of Shingon Buddhism, referred to as Ryujo in Japanese) arrived at a steel pagoda in southern India. He heard a melody seeping through the door of the tower and reverberating throughout the area. Nagarjuna realized that this melody was an expression of the universal truth resonating throughout the universe. Calling this a song of “praise,” (san) he described the process of learning this teaching as an act of enjoyment. In modern Shomyo, “san” continues to be a popular melody.

In ancient India, there were five sciences. Silpasthanavidya involved the arts and mathematics; Cikitsavidya involved medicine; Hetuvidya involved logic; Adhyatmavidya involved philosophy; and Shomyo involved phonology. Indian Shomyo came in the form of “Cabdra” (voice) and Vidya (knowledge) and focused on articulation and voicing. Turning to the scriptures, we find that the type of Shomyo practiced today existed long ago.

Shomyo originated in India and reached China and Japan with the spread of Buddhism. Songs created in India are called “Bonsan”; these were written in Sanskrit and then transliterated into Chinese, so it is impossible to decipher their meaning when read as-is. By contrast, “Kansan” are those songs that were composed in China or translated into Chinese.

Shomyo is an advanced system of vocal music. It even features musical scales, expressive techniques, and scores, each having complex rules of its own.

Shomyo has a pentatonic musical scale which is assigned names like the “Do,” “Re,” and “Mi” of Western music. They are kyu, sho, kaku, chi, and u. These are scaled across three octaves, producing a total of fifteen sounds. The three lowest tones and one highest tone are considered to be impossible to reproduce with the human voice, so there are in point of practice eleven tones.

Fifteen tones are scales across evently-spaced intervals.

There are several expressive ways of making the melody used in Shomyo richer. They are given various names, among them yuri, iro, sori, and atari. The vocal chords can be modulated in subtle ways to slowly ascend the musical scale or suddenly stop a tone. The subtleties of these techniques are extremely complex.

While Shomyo is used as a form of esoteric chant by monks in temples, it is a sophisticated musical format in its own right, with graceful and elegant melodies, robust rhythm, and the expression of joy and sorrow. Depending on the type of service being held, songs are selected that variously suggest joy, reminiscence, and other feelings.

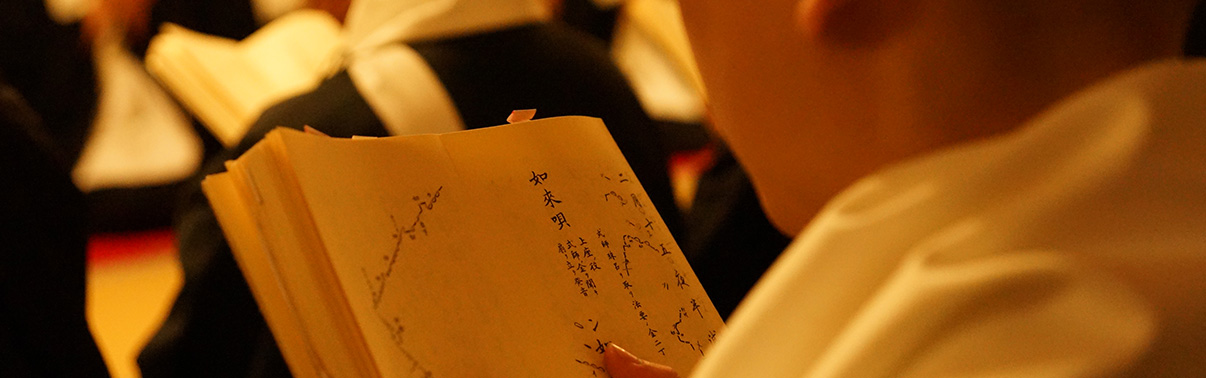

Shomyo uses musical scores. These describe the pentatonic scale and expressive form to be used and are called “hakase.” Following the rules of the hakase allows for performers to achieve a unified singing style.

At the same time properly learning Shomyo hinges on a very important aspect — oral traditions. There are rules not specifically written on the scores that are transmitted verbally from teacher to pupil. The act of special transmission outside the scriptures, from master to disciple, is a key point of the Shingon teachings in a wider sense.

Shomyo could be described as a form of music that expresses the joy of receiving the esoteric Buddhist teachings. During special rites, monks gather in the temple grounds and face the Buddha, adorning the occasion with chanted melodies. With its highly advanced formal system of music and an inner depth based on esoteric teachings, Shomyo carries on the Kobo Daishi’s 1,200 year old traditions and is a key component of Shingon Buddhism. As a sung form, it also acts as a medium for conveying the depth and richness of the Buddhist worldview to the laity.

In addition to Buddhist services, Kongobu-ji offers a range of opportunities for you to experience Shomyo chanting. We invite you to see what melodic prayer is like for yourself.

Koyasan Reihokan Museum

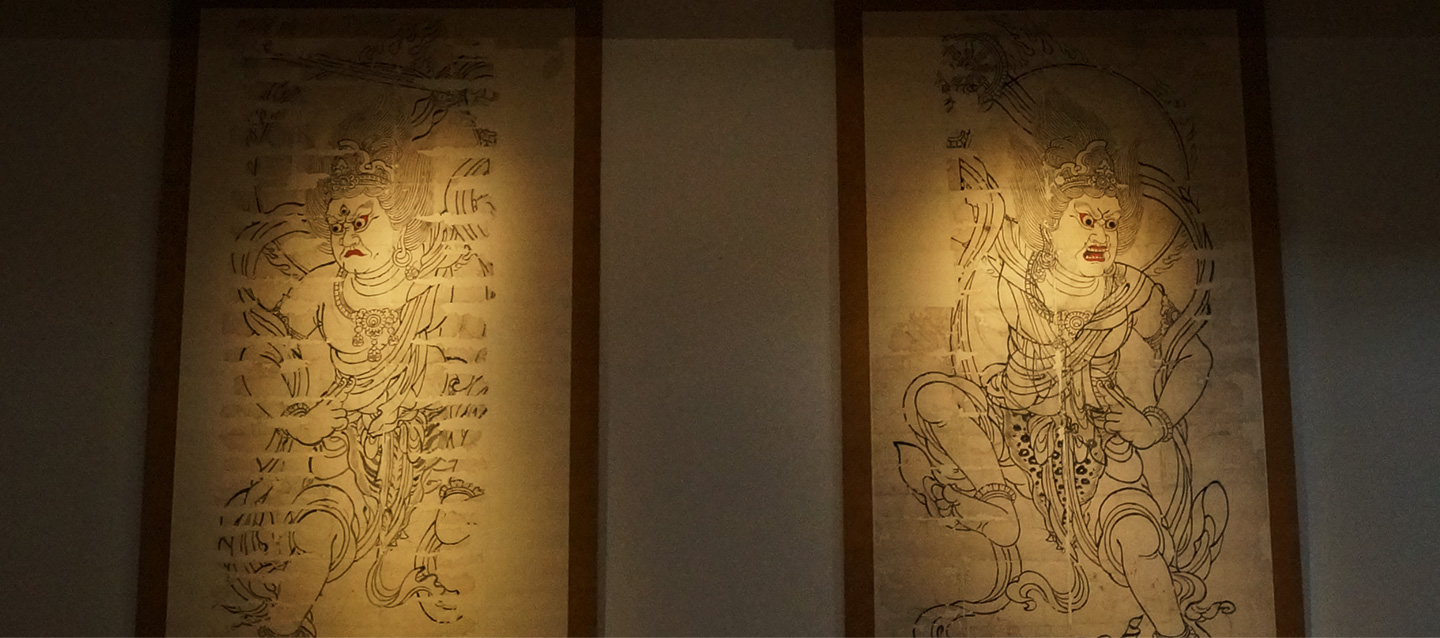

The Reihokan Museum is houses 50,000 cultural assets, among them twenty-one national treasures crafted over the 1,200 years of Mount Koya’s history. Each of these Buddhist sculptures, images, and writings is a physical testament to prayer and belief, carrying on the ideas of Mount Koya’s forebears into the present.

The Reihokan Museum was founded in 1921 in order to house and care for the cultural artifacts found throughout the mountain’s 117 various temples.

In recent years, the museum has simultaneously served to showcase these assets in public exhibits and broadcast the charms of Mount Koya far and wide.

The religious and historic value of the museum’s collection is indisputable. In addition, the pieces are richly expressive works of art that convey a non-linguistic, visual dimension to viewers from the world over.

In 2004, the sacred sites and pilgrimage routes in the Kii Mountain range were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Many people from the world over come to see them.

Mount Koya considers the unique esoteric Buddhist culture cultivated on the mountain to be a universal global asset to be shared with all. This ideal is transcending language, culture, and creed and drawing attention from people around the world.

Each of the pieces housed in the Koyasan Reihokan Museum tells part of the story of Mount Koya, inviting viewers into the glorious world of esoteric Buddhism.